EDDIE CANTOR, one of the most popular singer-comedians of the first half of the 20th century, began his career as a Lower East Side orphan. By 1933, he was earning enough money as a movie and radio star to move his young family to a penthouse triplex in one of the Upper West Side's signature buildings: the twin-towered San Remo Apartments on Central Park West and 74th Street.

Not long after the move, his adventurous 7-year-old daughter, Janet, clambered up the outside of the colonnaded south tower, where she hung with one hand from a metal rung 27 stories above Central Park West until her terrified nanny coaxed her down.

About 17 years later, Janet was married and living in an apartment just around the corner, where she conceived a son named Brian Gari.

Mr. Gari, now a lanky 54-year-old with a salt-and-pepper beard, today has an overview of the ever-evolving Upper West Side that is, in its way, nearly as commanding as was his mother's perspective from atop that tower. A singer-songwriter by profession, Mr. Gari has made a passionate lifelong hobby of documenting the changing streetscape of the Upper West Side, where he has lived all but a few months of his life. His primary method has been to collect every moving image of the neighborhood he could get his hands on, all the way back to a 1910 Edison Company film of Columbus Circle, along with scores of still photographs and salvaged scraps of demolished theaters.

Mr. Gari's fascination with the neighborhood's relentless evolution early. In 1964, at age 12, he was so struck by the wholesale demolitions taking place in the name of urban renewal that he traveled up and down Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues with an eight-millimeter camera, shooting a shaky but evocative 10-minute film he called ''City Slickin'.''

Twenty years later, as beloved theaters like the Loew's 83rd Street Quad were facing the wrecking ball, he grabbed a Betamovie camcorder and made another jostling photographic journey, this time down Broadway from West 91st Street past Columbus Circle. And ever since, each time he caught a film or video glimpse of the neighborhood, whether in a documentary of Rudolph Valentino's funeral at the Frank E. Campbell funeral home on Broadway in 1926 or a 1949 television episode of ''Candid Camera'' shot on West 103rd Street, he has saved them and ultimately digitized them for posterity.

''I hardly pay attention to the stories,'' Mr. Gari said one recent afternoon as he fast-forwarded through a 1963 television episode of the police drama ''Naked City'' that was playing on a hulking 50-inch television screen in his bedroom. ''I'm looking for the Upper West Side.''

He was sitting barefoot on a queen-size bed, surrounded by DVD's, film encyclopedias and photographs of his grandfather, in a rent-controlled apartment on West End Avenue near 92nd Street that has been his home since he moved there as a 12-year-old in 1964.

''This is Riverside Drive and the 70's,'' he said, explaining that ''Naked City'' was often shot around there because its production supervisor, Hal Schaffel, the father of a classmate of Mr. Gari's, lived on West End Avenue.

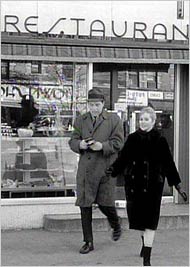

Noirish black-and-white images of a traffic accident and a murder whizzed past on the screen until Mr. Gari spotted the character Detective Adam Flint and his girlfriend coming out of a luncheonette called Steinberg's Dairy Restaurant, whose facade bore the number 2270. No street signs were visible.

''You see where this is?'' Mr. Gari asked excitedly. ''You see the reflection in the window? It's the Town Shop.'' He was referring to a celebrated lingerie store that opened in 1936 on the west side of Broadway near 82nd Street, and in 2002 moved three doors north on the same block.

Steinberg's was on the east side of Broadway, just across the street. On Mr. Gari's television screen the reflection in the restaurant's plate-glass window showed not only the reverse-image Art Deco sign of the Town Shop but also the shadowy reversed letters of Endicott Meats, which vanished from the street in 1989.

Twiddling his remote control, Mr. Gari froze the frame on fleeting images that revealed other 1963 shops on the east side of Broadway between 81st and 82nd Streets. North of Steinberg's stood Yee's Hand Laundry, a stationery shop, an unidentified store with prices in the window and a pizza place. These last two would be occupied from the mid-1970's to the early 1990's by Marvin Gardens, a popular restaurant. And today all these storefronts, including the Steinberg's site, are occupied by Laytner's Linen and Home.

''If you want to go back in time,'' Mr. Gari declared giddily, ''this is the episode to do it with.''

On the television screen, a dough-faced cabbie was trying to lure Detective Flint into a fistfight, but Mr. Gari didn't care about that. What really interested him was the mysterious shop on the northeast corner of West 82nd Street (the site today of a Liberty Travel agency) on whose sign he could only make out the letters ''West E.''

''West End?'' he asked aloud. ''A coffee shop, maybe?''

Unsatisfied, Mr. Gari froze the detective show and bounded out of the room, returning moments later with a crumbling 1966 phone book (he has 40 years' worth of old directories), which he inspected with the intensity of a monk poring over a rare religious manuscript.

''Aha!'' he finally announced. ''West End Fabrics.'' Mystery solved.

To spend hours watching Mr. Gari's moving images of the lost Upper West Side, and then to stroll along Broadway with him looking at today's storefronts, is to see the streetscape as an urban palimpsest, where remnants and recollections of the area's previous incarnations emerge unexpectedly, again and again, from beneath the current streetscape. The experience is like peering at the multilayered, weather-worn posters on a construction site's plywood fence, the top layer peeling away in places to reveal tantalizing scraps of the earlier images beneath it.

During an afternoon jaunt down Broadway, Mr. Gari stood outside a shiny Verizon Wireless store on the east side of the avenue near West 81st Street, a spot that in the 1963 ''Naked City'' episode was a bar and restaurant with a small metal awning. With a sweep of his hand, he pointed to other chain stores that in his opinion are robbing the Upper West Side of its individual character, making it increasingly less distinct from other neighborhoods.

On the west side of Broadway north of West 82nd Street, nearly the entire block -- home to at least seven shops in 1963, including a Plymouth clothing store and a Schrafft's -- was now taken up by Barnes & Noble and Talbots. On the southeast corner at 81st Street, the Italian Renaissance-style 1913 81st Street Theater building, where shows from vaudeville to ''Sesame Street'' were performed, was now occupied by what Mr. Gari sees as three prime examples of the Upper West Side's increasingly soulless homogenization. These are a Starbucks, a Staples and the lobby of the inevitable condominium, a high-rise built on the site of the old theater's auditorium, which had been a second structure located behind the surviving Broadway building.

Mr. Gari gestured toward a few filled holes in the terra cotta on the building's corner, where a huge ''RKO Keith's 81st Street'' sign was once anchored. ''To lose that building is sacrilegious,'' Mr. Gari grumbled, referring to the renovation of its interior. ''It's historic, and now it's just been gutted, and all you've got is the shell.''

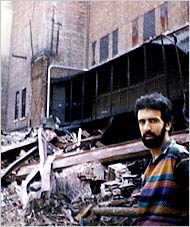

Perhaps because of his grandfather's five-decade run as a star, first on New York's theatrical stages and then in its movie houses, Mr. Gari has always felt a particular pang of loss any time an Upper West Side theater disappears. He has episodes of ''Naked City'' showing the Loew's 83rd Street movie palace in 1961 and 1963, and in 1984 he captured the theater on video a few months before it was knocked down to make way for the Bromley condominium.

After the theater's demolition, he poked around in the debris and found a certificate issued to the theater by the New York Edison Company in 1935.

''It's trash to people,'' Mr. Gari said with a chuckle. ''But to me it's history.''

Mr. Gari also rescued a heavy metal-and-glass ''Next Attraction'' sign from the New Yorker theater, on Broadway near 89th Street, as the revival house was being razed in 1985. And he picked up a video camera and ambled into the old Thalia theater, on 95th Street off Broadway, as that Art Deco theater was being gutted in 1999 -- until he was chased out by a beefy worker.

Among the places Eddie Cantor performed were theaters on the so-called Subway Circuit, which booked shows after their Broadway runs. One theater on the circuit was the Standard, later called the Stoddard, which was built in 1914 at 90th Street and Broadway. By the 1960's, the theater had become a supermarket, its marquee used to advertise specials on lobster tails and steer liver, as shown in documentary images Mr. Gari obtained from CBS.

After the supermarket, which had become a Food Emporium, was demolished in the mid-80's to make way for the New West apartment building and a new Food Emporium, Mr. Gari waded into the rubble. He emerged with a surprising vestige of the market's former incarnation: a 1961 form issued to the Stoddard Theater by the Workmen's Compensation Board.

But if the theater was once part of the Subway Circuit, where was the subway? Mr. Gari discovered the answer to that question in 1971, when he spotted a phantom platform and token booth while hurtling south on the subway from the 96th Street stop. For half a century beginning in 1904, the local IRT train stopped at Broadway and 91st Street, but as trains became longer, some stations were lengthened and others closed. The 91st Street station, rendered obsolete by the extension of the 96th Street platform, was shut down in 1959.

Standing on the northwest corner of West 91st Street and Broadway, Mr. Gari held up a 1940 photograph showing an ornate subway kiosk on that very spot. ''Wanna see?'' he asked, pointing to a small grate in the pavement. ''This is what's left of the 91st Street station.'' In the murk below the grate, one could make out an abandoned, dead-end staircase. ''Buried,'' Mr. Gari declared darkly.

One block downtown, Mr. Gari stood in front of the City Diner, previously the Argo coffee shop, on the northwest corner of Broadway and 90th Street. Buttoning up his TV Land jacket for warmth, he recalled a 1961 ''Naked City'' scene, shot north across 90th Street from the Standard Theater building, that showed a restaurant on the corner called Stark's. With a grin, he pointed out bolt holes still visible on City Diner's facade, beneath which could be discerned the all but invisible outline of the words Stark's Fine Foods.

Mr. Gari has produced 13 CD's of performances by his grandfather, and as he has delved into Mr. Cantor's life, he has been surprised to discover how often he himself has unwittingly trod the same Upper West Side turf that his grandfather did.

In 1963, as a sixth grader at the McBurney School on West 63rd Street, Mr. Gari cut gym for months to watch ''The Price Is Right,'' the television game show, as it was telecast up the street at the Colonial Theater on Broadway, north of West 62nd Street. Only years later did he learn that his grandfather performed there as far back as 1911, the year after Charlie Chaplin made his American debut on its stage. (The Colonial has since vanished and is now a nondescript public space called Harmony Atrium.)

When ''The Price Is Right'' moved to the Ritz Theater on West 48th Street, Mr. Gari followed, still regularly cutting gym. By coincidence, when his career led him to follow his grandfather to Broadway 23 years later, it was at the Ritz that ''Late Nite Comic,'' a short-lived 1987 musical for which Mr. Gari wrote the music and lyrics, was performed. Mr. Gari's account of the musical's bumpy production, ''We Bombed in New London,'' will be published in July.

A few months before he died in 1964, Mr. Cantor wrote a letter to his grandson, then 12, that Mr. Gari says provided a lift of creativity that would determine the direction of his life.

After expressing his eagerness to see his grandson's film of the West Side, Mr. Cantor wrote: ''From all appearances, it seems to me, you'll be the one to carry on the tradition of show business in the family.'' In October, the month his grandfather died, Mr. Gari wrote his first song. By the age of 15 he was traveling around the city by bus, selling his tunes to music publishers for $50 a pop.

One of the publishers he sometimes visited had its offices in the modern tower at 10 Columbus Circle (which, along with the adjoining New York Coliseum, was demolished in 2000 to make way for the Time Warner Center). More than three decades would pass before Mr. Gari discovered just how much meaning that site has held for his family across three generations.

About five years ago, Mr. Gari explained the other day as he walked in the shadow of the blue-glass Time Warner complex, someone told him that his grandfather regularly served as host of the NBC variety show ''The Colgate Comedy Hour,'' which was broadcast live from Columbus Circle. Mr. Gari's father, an actor and dancer named Roberto Gari, also performed in the show.

''The weird thing is,'' the son said, ''it didn't make sense to me, because I only knew Columbus Circle as post-1956.'' The notion of a theater there seemed mistaken.

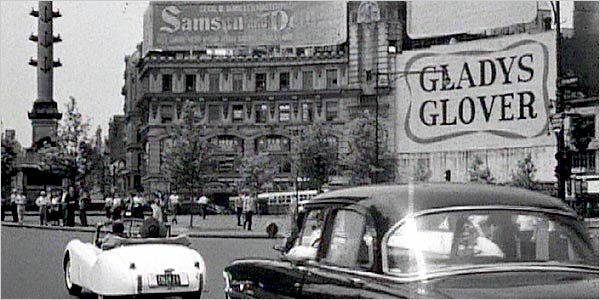

Then, four years ago, Mr. Gari had an epiphany while watching a 1954 Judy Holliday film called ''It Should Happen to You!'' In the movie, Holliday's character decides to have her name painted in giant letters on a billboard in Columbus Circle. And there, just south of the billboard, on the spot that in 1956 would become 10 Columbus Circle, could be seen the marquee of the International Theater, from which Mr. Cantor's highly rated television program was beamed to a national audience during the 1950-51 season.

''It was so important to me,'' Mr. Gari said, ''because I got to see a living, breathing picture of how this block looked with a theater here.''

Squinting with distaste at the gleaming 21st-century Time Warner Center, Mr. Gari pointed in the general direction of Stuart Weitzman, a shoe and handbag boutique on the ground floor.

''Right over there is where my grandfather did his show,'' he muttered. He wandered into the shiny mall inside the complex, then emerged a few minutes later with fresh evidence of just how mercilessly the city can expunge its past.

''Borders,'' he said ruefully, ''doesn't even carry an Eddie Cantor CD.'' E mail us at BrianGari@briangari.com!

In a 1954 Judy Holliday film, "It Should Happen to You!," with Peter Lawford, cameo appearances for long-gone Columbus Circle landmarks.By JOHN FREEMAN GILL (NY Times)

Published: May 14, 2006

Kino International/Brian Gari Archives

An image from a 1910 Edison Company film of Columbus Circle, one of Mr. Gari's rare finds.

The Secrets of 'Naked City'

Brian Gari Archives, 1964

Brian Gari Archives, 1964

In a 1963 episode of "Naked City," with Paul Burke as Detective Adam Flint and Nancy Malone as his girlfriend, Libby, a sign for the Town Shop is visible in reverse image.

Peeling Away the Present

Stops Along the Subway Circuit

Brian Gari, Eddie Cantor's grandson, retrieving memories after the Loew's 83rd Street theater was demolished in the mid-1980'sIn Search of a Personal Past

'You'll Be the One'